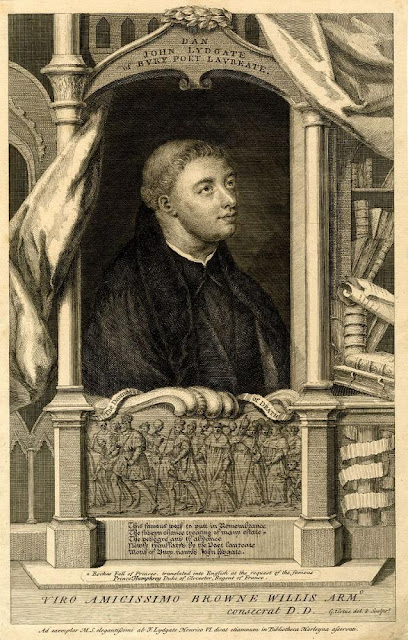

John Lydgate

John Lydgate, monk and poet, enjoyed significant fame during his lifetime, at times exceeding the reputation of Chaucer.

John Lydgate, (born c. 1370, Lidgate, Suffolk, Eng.—died c. 1450, Bury St. Edmunds?), English poet, known principally for long moralistic and devotional works.In his Testament Lydgate says that while still a boy he became a novice in the Benedictine abbey of Bury St. Edmunds, where he became a priest in 1397. He spent some time in London and Paris; but from 1415 he was mainly at Bury, except during 1421–32 when he was prior of Hatfield Broad Oak in Essex.Lydgate had few peers in his sheer productiveness; 145,000 lines of his verse survive. His only prose work, The Serpent of Division (1422), an account of Julius Caesar, is brief. His poems vary from vast narratives such as The Troy Book and The Falle of Princis to occasional poems of a few lines. Of the longer poems, one translated from the French, the allegory Reason and Sensuality (c. 1408) on the theme of chastity, contains fresh and charming descriptions of nature, in well-handled couplets. The Troy Book, begun in 1412 at the command of the prince of Wales, later Henry V, and finished in 1421, is a rendering of Guido delle Colonne’s Historia troiana. It was followed by The Siege of Thebes, in which the main story is drawn from a lost French romance, embellished by features from Boccaccio. - Britannica

It would seem that Lydgate has suffered from some undeserved negative press. Apparently, our day is not unique for producing pugilistic pundits who attack anything that challenges them to think with a measure of civility even while attempting a critique.

Before the middle of the seventeenth century his fame had evaporated and his name was all but forgotten. Few writers even mentioned him in the eighteenth century, although the few included Thomas Gray and Thomas Warton, both of whom had kind things to say about him.

Unfortunately this early attempt at rehabilitation was thwarted in 1802 by "scholar-at-arms" Joseph Ritson in one of the most brutally negative critiques ever written. To him Lydgate was a "voluminous, prosaick, and driveling monk" whose "stupid and fatiguing productions ... by no means deserve the name of poetry ... are neither worth collecting ... nor even worthy of preservation." Although pedantic, contentious, and eccentric, Ritson nevertheless was an indefatigable scholar and a meticulous editor of earlier English poetry. His forcefully expressed opinion of Lydgate was to influence critical opinion for the next 150 years. Scholars are still not totally free of it, although they now know, or should know, better. - Poetry Foundation

Was it Ritson's zealous vegetarianism activism, or his training in the adversarial system as a lawyer, or his allegiance to terror as a Jacobin that fueled his hostility towards Lydgate and others? Like his future wokeist kin, he took delight in subjecting his targets to a severe and very public bullying. As an analyst of literature, Ritson was exacting to the point of dehumanizing his chosen adversaries. If his contemporaries are to be believed, one might describe him as a type-A personality on crack. His unnecessarily caustic critiques raised much hostility toward him at the time. His glee in terrorizing others is not surprising given the Jacobin thrill at the beheading of anyone who dared to counter the revolutionary narrative. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose. Let's hope the current Jacobin siege doesn't last nearly as long as Ritson's unfounded critique of Lydgate.

A woodcut from an English blockbook, ca. 1495, depicting the Five Sacred Wounds of Christ.

The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

A liturgy restored to the Church in the Ordinariate Liturgy, Divine Worship, is the (Votive) Mass of the Five Wounds (DWM pp. 976-977).

The Collect reads:

O Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, who didst come down from heaven to earth from the bosom of the Father, and didst bear five wounds upon the Cross, and didst pour forth thy precious Blood for the remission of our sins: we humbly beseech thee that at the day of judgement we may be set at thy right hand, and hear from thee that most comfortable word, Come ye blessed into my Father's Kingdom; who livest and reignest with the Father, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, ever one God, world without end. Amen.

The Tract for the Mass is, in part, Psalm 43, the Judica Me prayed as the Preparation at the Foot of the Altar at Said Masses.

Lydgate wrote a brief poem on the Five Wounds of Christ:

At wells five, liquor I shall draw

To wash the rust of my sins quickly,

I mean the wells of Christ’s wounds five,

Whereby we claim of merciful pity.

John Lydgate and the Canterbury pilgrims leaving Canterbury, miniature from a manuscript containing The Troy Book and The Siege of Thebes, c. 1455–62. - Britannica

The Siege of Troy

Description of Physical Work (Archives Hub)

1 volume. ii + 174 + iii folios. Dimensions: 450 x 325 mm. Collation: 1-218, 22 six (ff. 169-74). Medium: vellum. Binding: purple velvet-covered boards, rebacked in the 19th century in purple morocco; single ornate gilt catchplate on foredge of upper board (clasp and hinge missing).

Scope and Content

A richly-decorated mid fifteenth-century manuscript of John Lydgate's Siege of Troy, containing numerous illuminations, with floriated borders, a half-page miniature at the beginning of each of the five books, and 64 other paintings.

Contents: John Lydgate, Siege of Troy, ed. H. Bergen, Lydgate's Troy book, A.D. 1412-20, 4 vols (1906-35): see Bibliography below. This copy is collated by Bergen as Cr. and is described in vol. 4, pp. 29-36. Index of Middle English verse, no. 2516/18. Bergen notes a special textual resemblance to Bodleian Library, Douce 230, which also contains the verses 'Pees makith plente...' (Index of Middle English verse, no. 2742: printed by Bergen, vol. 4, p. 26). f. 174 is blank except for the arms of the Carent family on the recto.

Script: Gothic bastard secretary with anglicana influence (a), by two hands. The second hand begins at f. 113r, col. b, line 27, at the words 'And of my herte' (Bergen edition, vol. 4, line 189): in this and the next 69 lines (lines 189-257) the new scribe uses the punctus elevatus as a mark of punctuation within the line, instead of //. Written space: 305 x 200 mm. 2 columns, 44 lines at first, 43 from f. 89 (beginning of quire 11) and 45 from f. 113 (beginning of quire 14).

Comments

Post a Comment

Your comments will be appreciated and posted if 1) they are on topic and 2) preserve decorum.

Stand by your word.